Donald Trump has picked former soccer participant Scott Turner to steer the U.S. Division of Housing and City Building. Whilst no longer a lot is understood about TurnerŌĆÖs positions as he awaits affirmation via the Senate, TrumpŌĆÖs variety attracts consideration to the incoming managementŌĆÖs housing insurance policies.

The ones insurance policies, obvious in each the primary Trump presidency and in feedback made all over the marketing campaign, recommend an abiding religion within the non-public sector and native executive. And theyŌĆÖre prone to come with deregulation and tax breaks for funding in distressed spaces.

In addition they display a disdain for federal truthful housing systems. Those systems, Trump mentioned at the marketing campaign path in 2020, are ŌĆ£bringing who knows into your suburbs, so your communities will be unsafe and your housing values will go down.ŌĆØ

ŌĆśInharmonious neighborsŌĆÖ

In his September 2024 debate with Kamala Harris, Trump replied to a query on immigration via amplifying the discredited rumor that Haitian immigrants in Ohio had been ŌĆ£eating the pets of the people that live there.ŌĆØ

ŌĆ£This is whatŌĆÖs happening in our country,ŌĆØ he added, ŌĆ£and itŌĆÖs a shame.ŌĆØ

As a historian of public coverage fascinated about city inequality, IŌĆÖm struck via the similarity between TrumpŌĆÖs diatribe and the ideals that instituted racial segregation in housing a century in the past.

TrumpŌĆÖs false declare echoes the long-standing anxieties of white house owners referring to immigration normally and African American migration particularly.

Mia Perez, left, an immigration attorney, and Bernardette Dor, a pastor on the First Haitian Church, pose in combination after becoming a member of a prayer stroll in improve in their Haitian immigrant group in Springfield, Ohio, on Sept. 14, 2024.

AP Photograph/Luis Andres Henao

Each circumstances pit the pursuits of 1 set of citizens in opposition to the ones of some other.

First, there are the established, overwhelmingly white, citizens ŌĆō in TrumpŌĆÖs lingo, ŌĆ£the people that live there.ŌĆØ Then come the undesirable new arrivals whose surprising presence in American neighborhoods is noticed as a risk to public well being, welfare and belongings values.

Traditionally, the threats posed via ŌĆ£inharmoniousŌĆØ neighbors ŌĆō as actual property brokers and later federal housing businesses put it ŌĆō have fascinated about immigrants and African American citizens.

The surge in immigration to the U.S. on the finish of the nineteenth century animated a notoriously nativist reaction from native governments and realty teams. It integrated early efforts at land-use zoning geared toward setting up economically and racially unique residential districts in towns. And it concerned the primary stirrings of white flight to the suburbs, particularly within the unexpectedly urbanizing Northeast and Midwest.

Patchwork apartheid

Nevertheless it was once the Nice Migration of African American citizens within the first many years of the 20 th century, coupled with the city residential increase of the Twenties, that galvanized the peculiarly American alchemy of race and belongings.

All over this era, many towns, starting with Baltimore in 1910, experimented with explicitly racial zoning that designated neighborhoods for only white or Black occupancy.

The Ultimate Court docket struck those rules down in 1917 at the grounds that it invaded ŌĆ£the civil right to acquire, enjoy and use property.ŌĆØ

With the choice of legally codified racial zoning closed, as I element in my e-book, ŌĆ£Patchwork Apartheid,ŌĆØ the white response to the Nice Migration grew to become to the non-public and piecemeal motion of builders, actual property brokers and house owners.

The center piece was once the fashionable use of personal contracts designed to stop the ones ŌĆ£not wholly of the Caucasian raceŌĆØ from proudly owning or occupying houses in ŌĆ£protectedŌĆØ neighborhoods.

This non-public resistance to built-in neighborhoods was once happening as new housing begins ballooned after the battle, from 240,000 a yr in 1920 to nearly 1 million in 1925.

Those restrictions took various paperwork.

Suburban builders frequently imposed prohibitions on African American occupancy or possession of recent development, particularly within the unexpectedly rising towns of the Midwest. Current citizens of older neighborhoods dealing with racial transition in puts equivalent to Chicago and St. Louis would additionally impose racial covenants via petition.

In these types of settings, as I element in my e-book, racial restrictions had been mechanically hooked up to particular person house gross sales via patrons, dealers or actual property brokers. They was hoping to push back what white realty pursuits mechanically known as ŌĆ£invasionŌĆØ or ŌĆ£encroachment.ŌĆØ

The end result was once a type of patchwork apartheid. It was once crafted national however stitched in combination parcel via parcel, block via block, subdivision via subdivision.

Stark racial segregation

My paintings on St. Louis has exposed virtually 2,000 racially restrictive agreements imposed between 1900 and 1950. Via 1950, this patchwork of personal restriction encompassed just about two-thirds of the St. Louis areaŌĆÖs residential homes.

Their core good judgment was once that occupancy via inharmonious neighbors constituted a ŌĆ£nuisanceŌĆØ use of belongings.

Ahead of 1920, non-public belongings restrictions frequently integrated a common nuisance provision barring business makes use of, incessantly checklist trades offensive to the senses, equivalent to a slaughterhouse or a junkyard, or to at least oneŌĆÖs morals, equivalent to a tavern.

According to the Nice Migration, white realty corporations in St. Louis and in different places merely appended ŌĆ£coloredŌĆØ occupancy to their checklist of nuisances.

For instance, the uniform settlement utilized by the St. Louis Actual Property Alternate banned two categories of patrons or renters: ŌĆ£any slaughterhouse, junkshop, or rag-picking establishmentŌĆØ and ŌĆ£a Negro or Negroes.ŌĆØ

Within the St. Louis subdivision of Cleveland Heights, a protracted checklist of proscribed nuisances was once capped with the availability that no lot may ŌĆ£in any way or mannerŌĆØ be ŌĆ£occupied by any persons other than those of the Caucasian Race.ŌĆØ

Some restrictions elided racial classes and nuisances via proscribing gross sales to citizens regarded as merely ŌĆ£objectionableŌĆØ or ŌĆ£undesirable.ŌĆØ

A not unusual clause present in maximum Midwestern settings barred any ŌĆ£race or nationality other than those for whom the premises are intended.ŌĆØ

Such non-public restrictions had been dominated an unenforceable violation of equivalent coverage via the Ultimate Court docket in 1948. They usually had been prohibited outright via the Truthful Housing Act twenty years later.

However the injury ŌĆō stark racial segregation and a yawning racial wealth hole ŌĆō was once completed. And the core assumptions about race and belongings lived on within the insurance policies of personal realty, lending and appraisal.

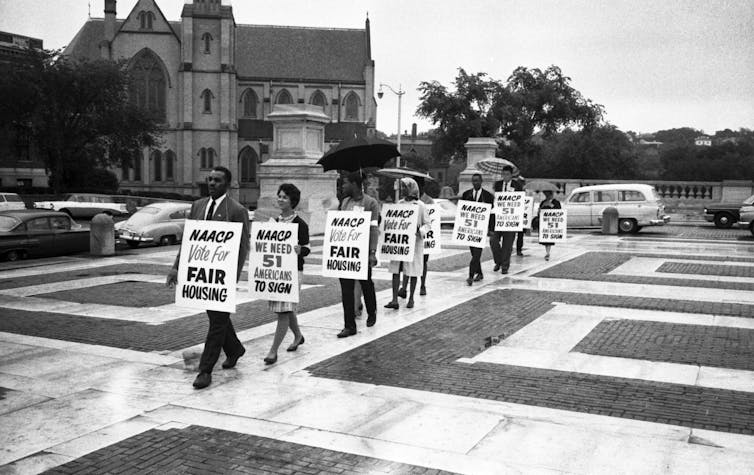

Contributors of the NAACP wooden the Rhode Island State Space in improve of truthful housing regulation in Windfall on June 10, 1963.

Photograph via Bettmann Archive/Getty Pictures

ŌĆśYour communities will be unsafeŌĆÖ

TrumpŌĆÖs debate outburst, on this appreciate, mirrored a racial politics formed as a lot via his actual property background as his political aspirations.

Trump inherited a belongings portfolio from his father that was once already deeply dedicated to racial segregation and discrimination in opposition to African American tenants. Starting within the Seventies, his circle of relativesŌĆÖs New York realty observe was once infamous, and mechanically sued, for violations of the 1968 Truthful Housing Act, supposed to test non-public discrimination in non-public realty.

As president, Trump persevered to erode the perception of truthful housing for all.

In 2020, he jettisoned an Obama-era rule requiring that towns receiving federal housing budget affirmatively cope with native discrimination and segregation.

ŌĆ£The suburb destruction,ŌĆØ he promised on the time, ŌĆ£will end with us.ŌĆØ

Trump housing 2.0

Turner, as the following HUD secretary, is poised to pick out up the place the primary Trump management left off.

Imagine the housing time table of Undertaking 2025, the Heritage BasisŌĆÖs sweeping blueprint for the second one Trump management. Penned via Ben Carson, TrumpŌĆÖs first HUD secretary, it proposes an intensive retreat from federal ŌĆ£overreachŌĆØ that would come with gutting anti-discrimination provisions in federal systems and deferring to localities on zoning.

It could additionally bar noncitizens from public housing and opposite ŌĆ£all actions taken by the Biden Administration to advance progressive ideology.ŌĆØ

On the time of TrumpŌĆÖs Springfield, Ohio, feedback, the apocryphal specter of pet-eating immigrants gave the impression however yet one more oddity in a marketing campaign punctuated with them.

Nevertheless it was once greater than that. It was once the preamble to a brand new bankruptcy within the U.S.ŌĆÖs lengthy historical past of discriminatory group ŌĆ£restrictionŌĆØ or ŌĆ£protection.ŌĆØ